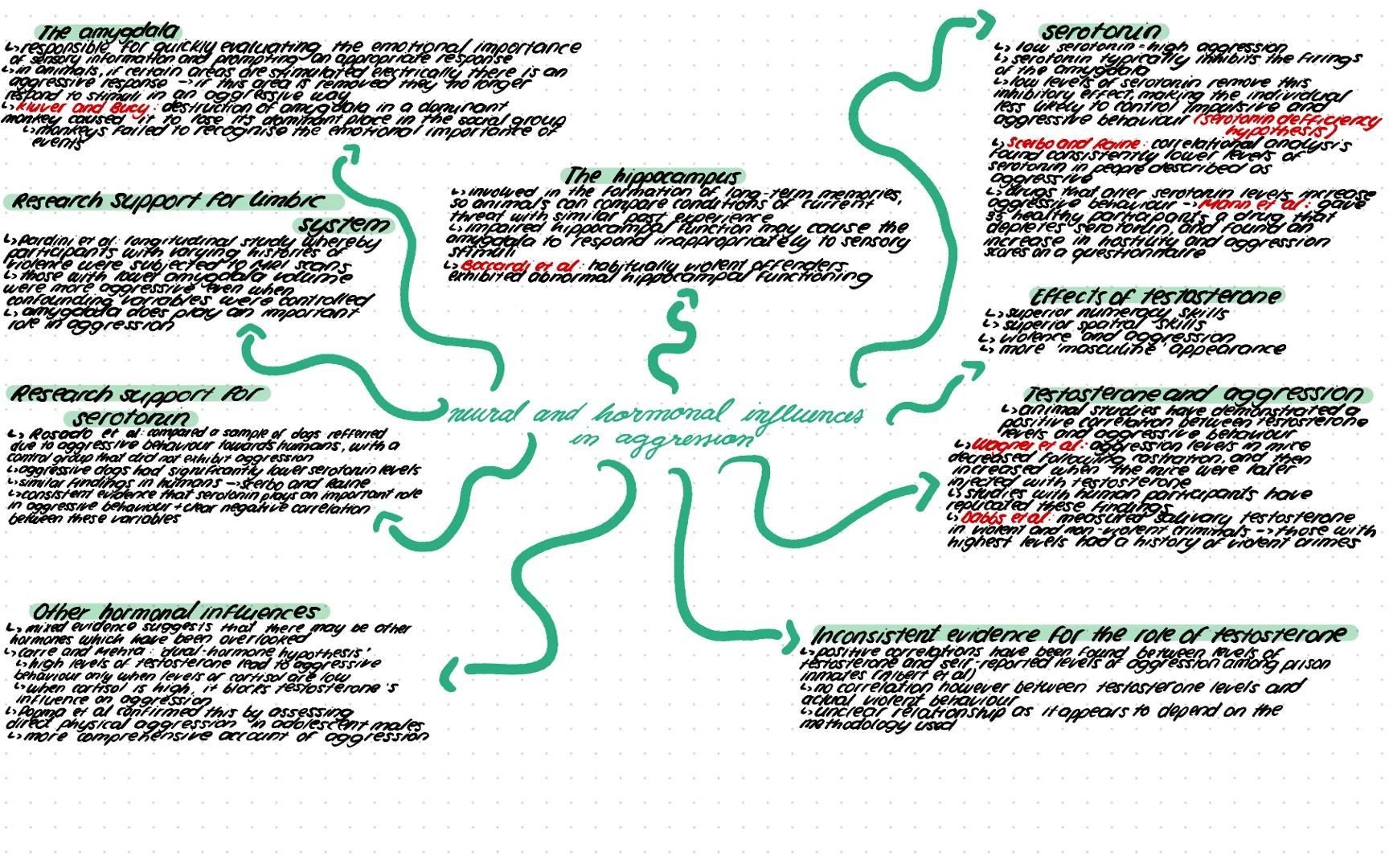

Brain Structures and Hormones in Aggression

The limbic system contains two vital structures that regulate aggressive responses. The amygdala quickly evaluates the emotional importance of sensory information and triggers appropriate responses. When damaged, it disrupts this evaluation process. Kluver and Bucy found that destroying the amygdala in a dominant monkey caused it to misinterpret emotional cues. Similarly, the hippocampus forms long-term memories that help compare current threats with past experiences, with impaired function potentially causing inappropriate amygdala responses.

Serotonin plays a crucial inhibitory role in aggression. The "serotonin deficiency hypothesis" suggests that low levels of this neurotransmitter remove the inhibitory effect on the amygdala, making individuals less likely to control impulsive aggressive behaviour. Research consistently shows a negative correlation between serotonin levels and aggression. Rosado's study with aggressive dogs found significantly lower serotonin levels compared to non-aggressive controls, with similar findings replicated in humans.

Testosterone has been linked to aggression in numerous studies, though with some inconsistencies. Wagner's research showed aggression levels in mice decreased when testosterone was lowered and increased when raised. In humans, Dabbs found that violent criminals had higher salivary testosterone levels than non-violent offenders. However, the relationship isn't straightforward – some studies show correlations with self-reported aggression but not with actual violent behaviour.

Remember this! The relationship between hormones and aggression is more complex than initially thought. The dual-hormone hypothesis suggests high testosterone leads to aggression only when cortisol levels are low. When cortisol is high, it appears to block testosterone's influence on aggressive behaviour.

Recent research points to a more nuanced understanding of hormonal influences. The dual-hormone hypothesis proposed by Carre and Mehta suggests testosterone's relationship with aggression depends on cortisol levels. This provides a more comprehensive explanation of why testosterone doesn't always predict aggressive behaviour - context and other hormones matter too!