Criminal law cases involving assault and battery form the backbone... Show more

Sign up to see the contentIt's free!

Access to all documents

Improve your grades

Join milions of students

By signing up you accept Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Subjects

Classic Dramatic Literature

Modern Lyric Poetry

Influential English-Language Authors

Classic and Contemporary Novels

Literary Character Analysis

Romantic and Love Poetry

Reading Analysis and Interpretation

Evidence Analysis and Integration

Author's Stylistic Elements

Figurative Language and Rhetoric

Show all topics

Human Organ Systems

Cellular Organization and Development

Biomolecular Structure and Organization

Enzyme Structure and Regulation

Cellular Organization Types

Biological Homeostatic Processes

Cellular Membrane Structure

Autotrophic Energy Processes

Environmental Sustainability and Impact

Neural Communication Systems

Show all topics

Social Sciences Research & Practice

Social Structure and Mobility

Classic Social Influence Experiments

Social Systems Theories

Family and Relationship Dynamics

Memory Systems and Processes

Neural Bases of Behavior

Social Influence and Attraction

Psychotherapeutic Approaches

Human Agency and Responsibility

Show all topics

Chemical Sciences and Applications

Chemical Bond Types and Properties

Organic Functional Groups

Atomic Structure and Composition

Chromatographic Separation Principles

Chemical Compound Classifications

Electrochemical Cell Systems

Periodic Table Organization

Chemical Reaction Kinetics

Chemical Equation Conservation

Show all topics

Nazi Germany and Holocaust 1933-1945

World Wars and Peace Treaties

European Monarchs and Statesmen

Cold War Global Tensions

Medieval Institutions and Systems

European Renaissance and Enlightenment

Modern Global Environmental-Health Challenges

Modern Military Conflicts

Medieval Migration and Invasions

World Wars Era and Impact

Show all topics

790

•

11 Feb 2026

•

sidra

@s1dra_h

Criminal law cases involving assault and battery form the backbone... Show more

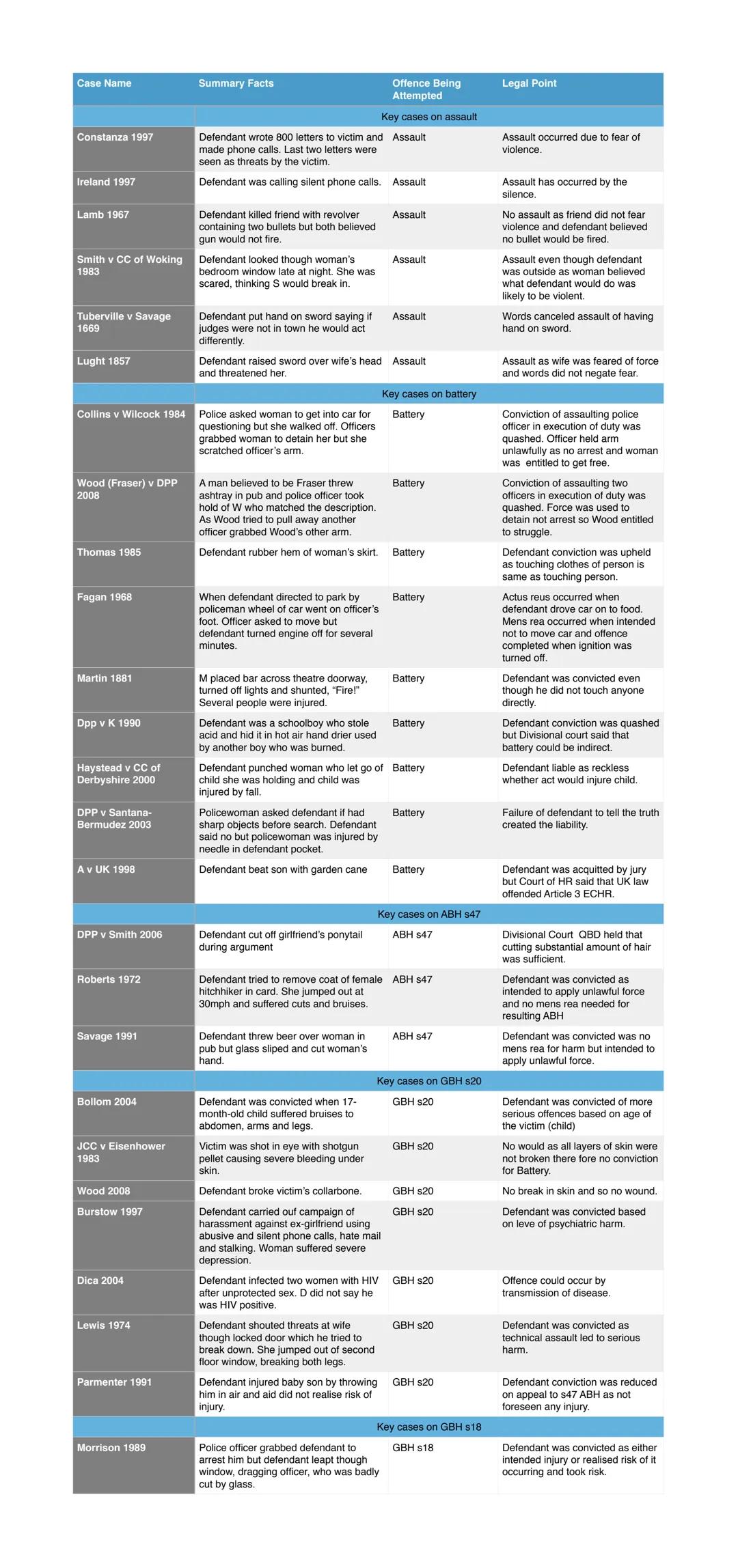

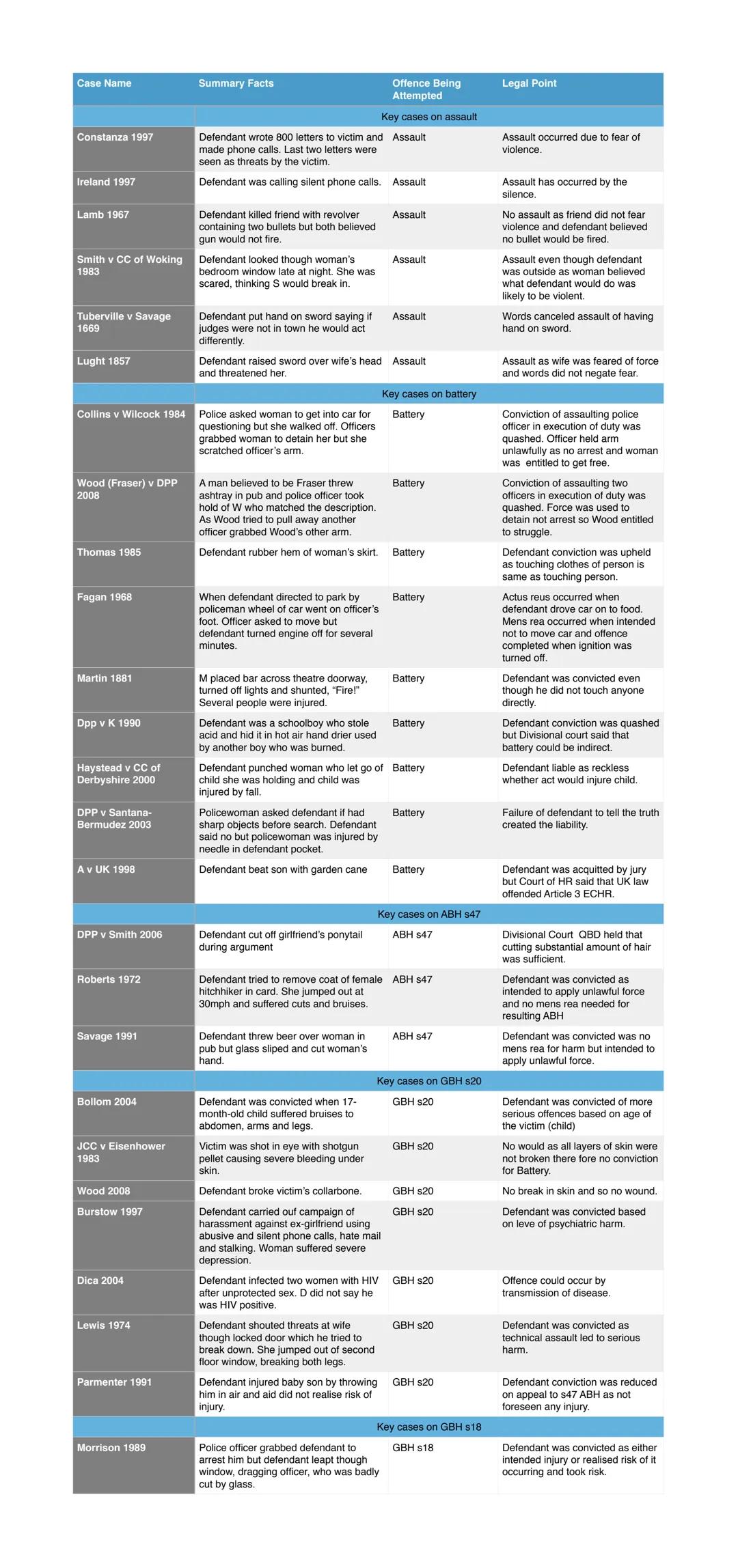

Ever wondered how the law decides whether someone's threatening behaviour counts as a crime? These cases show exactly how courts draw the line between different types of violent offences.

Assault cases demonstrate that you don't need to actually touch someone to commit a crime. In Constanza (1997), 800 threatening letters were enough to constitute assault because the victim feared violence. Even silent phone calls can be assault, as shown in Ireland (1997). However, the victim must genuinely fear immediate violence - in Lamb (1967), no assault occurred because both people thought the gun wouldn't fire.

Battery cases focus on unlawful touching or contact. The famous Fagan (1968) case shows how driving onto a police officer's foot became battery when the defendant refused to move the car. Interestingly, battery can be indirect - in Martin (1881), causing a stampede by shouting "Fire!" in a theatre was still battery even though the defendant didn't touch anyone directly.

Remember: Assault is about fear of violence, whilst battery involves actual unlawful contact - even if it's indirect!

The courts have established that touching someone's clothing counts as touching them (Thomas 1985), and failing to disclose dangers like needles in pockets can create liability . These cases show how mens rea (criminal intent) and actus reus (criminal act) work together to establish guilt.

More serious offences like ABH (s47) and GBH build on these basic principles. Cases like Roberts (1972) show that defendants can be liable even when victims injure themselves trying to escape, whilst Burstow (1997) established that severe psychiatric harm can constitute grievous bodily harm.

Our AI Companion is a student-focused AI tool that offers more than just answers. Built on millions of Knowunity resources, it provides relevant information, personalised study plans, quizzes, and content directly in the chat, adapting to your individual learning journey.

You can download the app from Google Play Store and Apple App Store.

That's right! Enjoy free access to study content, connect with fellow students, and get instant help – all at your fingertips.

App Store

Google Play

The app is very easy to use and well designed. I have found everything I was looking for so far and have been able to learn a lot from the presentations! I will definitely use the app for a class assignment! And of course it also helps a lot as an inspiration.

Stefan S

iOS user

This app is really great. There are so many study notes and help [...]. My problem subject is French, for example, and the app has so many options for help. Thanks to this app, I have improved my French. I would recommend it to anyone.

Samantha Klich

Android user

Wow, I am really amazed. I just tried the app because I've seen it advertised many times and was absolutely stunned. This app is THE HELP you want for school and above all, it offers so many things, such as workouts and fact sheets, which have been VERY helpful to me personally.

Anna

iOS user

Best app on earth! no words because it’s too good

Thomas R

iOS user

Just amazing. Let's me revise 10x better, this app is a quick 10/10. I highly recommend it to anyone. I can watch and search for notes. I can save them in the subject folder. I can revise it any time when I come back. If you haven't tried this app, you're really missing out.

Basil

Android user

This app has made me feel so much more confident in my exam prep, not only through boosting my own self confidence through the features that allow you to connect with others and feel less alone, but also through the way the app itself is centred around making you feel better. It is easy to navigate, fun to use, and helpful to anyone struggling in absolutely any way.

David K

iOS user

The app's just great! All I have to do is enter the topic in the search bar and I get the response real fast. I don't have to watch 10 YouTube videos to understand something, so I'm saving my time. Highly recommended!

Sudenaz Ocak

Android user

In school I was really bad at maths but thanks to the app, I am doing better now. I am so grateful that you made the app.

Greenlight Bonnie

Android user

very reliable app to help and grow your ideas of Maths, English and other related topics in your works. please use this app if your struggling in areas, this app is key for that. wish I'd of done a review before. and it's also free so don't worry about that.

Rohan U

Android user

I know a lot of apps use fake accounts to boost their reviews but this app deserves it all. Originally I was getting 4 in my English exams and this time I got a grade 7. I didn’t even know about this app three days until the exam and it has helped A LOT. Please actually trust me and use it as I’m sure you too will see developments.

Xander S

iOS user

THE QUIZES AND FLASHCARDS ARE SO USEFUL AND I LOVE Knowunity AI. IT ALSO IS LITREALLY LIKE CHATGPT BUT SMARTER!! HELPED ME WITH MY MASCARA PROBLEMS TOO!! AS WELL AS MY REAL SUBJECTS ! DUHHH 😍😁😲🤑💗✨🎀😮

Elisha

iOS user

This apps acc the goat. I find revision so boring but this app makes it so easy to organize it all and then you can ask the freeeee ai to test yourself so good and you can easily upload your own stuff. highly recommend as someone taking mocks now

Paul T

iOS user

The app is very easy to use and well designed. I have found everything I was looking for so far and have been able to learn a lot from the presentations! I will definitely use the app for a class assignment! And of course it also helps a lot as an inspiration.

Stefan S

iOS user

This app is really great. There are so many study notes and help [...]. My problem subject is French, for example, and the app has so many options for help. Thanks to this app, I have improved my French. I would recommend it to anyone.

Samantha Klich

Android user

Wow, I am really amazed. I just tried the app because I've seen it advertised many times and was absolutely stunned. This app is THE HELP you want for school and above all, it offers so many things, such as workouts and fact sheets, which have been VERY helpful to me personally.

Anna

iOS user

Best app on earth! no words because it’s too good

Thomas R

iOS user

Just amazing. Let's me revise 10x better, this app is a quick 10/10. I highly recommend it to anyone. I can watch and search for notes. I can save them in the subject folder. I can revise it any time when I come back. If you haven't tried this app, you're really missing out.

Basil

Android user

This app has made me feel so much more confident in my exam prep, not only through boosting my own self confidence through the features that allow you to connect with others and feel less alone, but also through the way the app itself is centred around making you feel better. It is easy to navigate, fun to use, and helpful to anyone struggling in absolutely any way.

David K

iOS user

The app's just great! All I have to do is enter the topic in the search bar and I get the response real fast. I don't have to watch 10 YouTube videos to understand something, so I'm saving my time. Highly recommended!

Sudenaz Ocak

Android user

In school I was really bad at maths but thanks to the app, I am doing better now. I am so grateful that you made the app.

Greenlight Bonnie

Android user

very reliable app to help and grow your ideas of Maths, English and other related topics in your works. please use this app if your struggling in areas, this app is key for that. wish I'd of done a review before. and it's also free so don't worry about that.

Rohan U

Android user

I know a lot of apps use fake accounts to boost their reviews but this app deserves it all. Originally I was getting 4 in my English exams and this time I got a grade 7. I didn’t even know about this app three days until the exam and it has helped A LOT. Please actually trust me and use it as I’m sure you too will see developments.

Xander S

iOS user

THE QUIZES AND FLASHCARDS ARE SO USEFUL AND I LOVE Knowunity AI. IT ALSO IS LITREALLY LIKE CHATGPT BUT SMARTER!! HELPED ME WITH MY MASCARA PROBLEMS TOO!! AS WELL AS MY REAL SUBJECTS ! DUHHH 😍😁😲🤑💗✨🎀😮

Elisha

iOS user

This apps acc the goat. I find revision so boring but this app makes it so easy to organize it all and then you can ask the freeeee ai to test yourself so good and you can easily upload your own stuff. highly recommend as someone taking mocks now

Paul T

iOS user

sidra

@s1dra_h

Criminal law cases involving assault and battery form the backbone of understanding how the legal system handles violence and harm. These landmark cases show how courts have interpreted everything from threatening letters to serious physical injuries, helping define the boundaries... Show more

Access to all documents

Improve your grades

Join milions of students

By signing up you accept Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Ever wondered how the law decides whether someone's threatening behaviour counts as a crime? These cases show exactly how courts draw the line between different types of violent offences.

Assault cases demonstrate that you don't need to actually touch someone to commit a crime. In Constanza (1997), 800 threatening letters were enough to constitute assault because the victim feared violence. Even silent phone calls can be assault, as shown in Ireland (1997). However, the victim must genuinely fear immediate violence - in Lamb (1967), no assault occurred because both people thought the gun wouldn't fire.

Battery cases focus on unlawful touching or contact. The famous Fagan (1968) case shows how driving onto a police officer's foot became battery when the defendant refused to move the car. Interestingly, battery can be indirect - in Martin (1881), causing a stampede by shouting "Fire!" in a theatre was still battery even though the defendant didn't touch anyone directly.

Remember: Assault is about fear of violence, whilst battery involves actual unlawful contact - even if it's indirect!

The courts have established that touching someone's clothing counts as touching them (Thomas 1985), and failing to disclose dangers like needles in pockets can create liability . These cases show how mens rea (criminal intent) and actus reus (criminal act) work together to establish guilt.

More serious offences like ABH (s47) and GBH build on these basic principles. Cases like Roberts (1972) show that defendants can be liable even when victims injure themselves trying to escape, whilst Burstow (1997) established that severe psychiatric harm can constitute grievous bodily harm.

Our AI Companion is a student-focused AI tool that offers more than just answers. Built on millions of Knowunity resources, it provides relevant information, personalised study plans, quizzes, and content directly in the chat, adapting to your individual learning journey.

You can download the app from Google Play Store and Apple App Store.

That's right! Enjoy free access to study content, connect with fellow students, and get instant help – all at your fingertips.

13

Smart Tools NEW

Transform this note into: ✓ 50+ Practice Questions ✓ Interactive Flashcards ✓ Full Mock Exam ✓ Essay Outlines

App Store

Google Play

The app is very easy to use and well designed. I have found everything I was looking for so far and have been able to learn a lot from the presentations! I will definitely use the app for a class assignment! And of course it also helps a lot as an inspiration.

Stefan S

iOS user

This app is really great. There are so many study notes and help [...]. My problem subject is French, for example, and the app has so many options for help. Thanks to this app, I have improved my French. I would recommend it to anyone.

Samantha Klich

Android user

Wow, I am really amazed. I just tried the app because I've seen it advertised many times and was absolutely stunned. This app is THE HELP you want for school and above all, it offers so many things, such as workouts and fact sheets, which have been VERY helpful to me personally.

Anna

iOS user

Best app on earth! no words because it’s too good

Thomas R

iOS user

Just amazing. Let's me revise 10x better, this app is a quick 10/10. I highly recommend it to anyone. I can watch and search for notes. I can save them in the subject folder. I can revise it any time when I come back. If you haven't tried this app, you're really missing out.

Basil

Android user

This app has made me feel so much more confident in my exam prep, not only through boosting my own self confidence through the features that allow you to connect with others and feel less alone, but also through the way the app itself is centred around making you feel better. It is easy to navigate, fun to use, and helpful to anyone struggling in absolutely any way.

David K

iOS user

The app's just great! All I have to do is enter the topic in the search bar and I get the response real fast. I don't have to watch 10 YouTube videos to understand something, so I'm saving my time. Highly recommended!

Sudenaz Ocak

Android user

In school I was really bad at maths but thanks to the app, I am doing better now. I am so grateful that you made the app.

Greenlight Bonnie

Android user

very reliable app to help and grow your ideas of Maths, English and other related topics in your works. please use this app if your struggling in areas, this app is key for that. wish I'd of done a review before. and it's also free so don't worry about that.

Rohan U

Android user

I know a lot of apps use fake accounts to boost their reviews but this app deserves it all. Originally I was getting 4 in my English exams and this time I got a grade 7. I didn’t even know about this app three days until the exam and it has helped A LOT. Please actually trust me and use it as I’m sure you too will see developments.

Xander S

iOS user

THE QUIZES AND FLASHCARDS ARE SO USEFUL AND I LOVE Knowunity AI. IT ALSO IS LITREALLY LIKE CHATGPT BUT SMARTER!! HELPED ME WITH MY MASCARA PROBLEMS TOO!! AS WELL AS MY REAL SUBJECTS ! DUHHH 😍😁😲🤑💗✨🎀😮

Elisha

iOS user

This apps acc the goat. I find revision so boring but this app makes it so easy to organize it all and then you can ask the freeeee ai to test yourself so good and you can easily upload your own stuff. highly recommend as someone taking mocks now

Paul T

iOS user

The app is very easy to use and well designed. I have found everything I was looking for so far and have been able to learn a lot from the presentations! I will definitely use the app for a class assignment! And of course it also helps a lot as an inspiration.

Stefan S

iOS user

This app is really great. There are so many study notes and help [...]. My problem subject is French, for example, and the app has so many options for help. Thanks to this app, I have improved my French. I would recommend it to anyone.

Samantha Klich

Android user

Wow, I am really amazed. I just tried the app because I've seen it advertised many times and was absolutely stunned. This app is THE HELP you want for school and above all, it offers so many things, such as workouts and fact sheets, which have been VERY helpful to me personally.

Anna

iOS user

Best app on earth! no words because it’s too good

Thomas R

iOS user

Just amazing. Let's me revise 10x better, this app is a quick 10/10. I highly recommend it to anyone. I can watch and search for notes. I can save them in the subject folder. I can revise it any time when I come back. If you haven't tried this app, you're really missing out.

Basil

Android user

This app has made me feel so much more confident in my exam prep, not only through boosting my own self confidence through the features that allow you to connect with others and feel less alone, but also through the way the app itself is centred around making you feel better. It is easy to navigate, fun to use, and helpful to anyone struggling in absolutely any way.

David K

iOS user

The app's just great! All I have to do is enter the topic in the search bar and I get the response real fast. I don't have to watch 10 YouTube videos to understand something, so I'm saving my time. Highly recommended!

Sudenaz Ocak

Android user

In school I was really bad at maths but thanks to the app, I am doing better now. I am so grateful that you made the app.

Greenlight Bonnie

Android user

very reliable app to help and grow your ideas of Maths, English and other related topics in your works. please use this app if your struggling in areas, this app is key for that. wish I'd of done a review before. and it's also free so don't worry about that.

Rohan U

Android user

I know a lot of apps use fake accounts to boost their reviews but this app deserves it all. Originally I was getting 4 in my English exams and this time I got a grade 7. I didn’t even know about this app three days until the exam and it has helped A LOT. Please actually trust me and use it as I’m sure you too will see developments.

Xander S

iOS user

THE QUIZES AND FLASHCARDS ARE SO USEFUL AND I LOVE Knowunity AI. IT ALSO IS LITREALLY LIKE CHATGPT BUT SMARTER!! HELPED ME WITH MY MASCARA PROBLEMS TOO!! AS WELL AS MY REAL SUBJECTS ! DUHHH 😍😁😲🤑💗✨🎀😮

Elisha

iOS user

This apps acc the goat. I find revision so boring but this app makes it so easy to organize it all and then you can ask the freeeee ai to test yourself so good and you can easily upload your own stuff. highly recommend as someone taking mocks now

Paul T

iOS user